NEW YORK – The blue courts are hard, the resolve of a red-hot Spanish conquistador named Nadal is harder, and the internationally-flavored guys and dolls are in town playing tennis again. Their fortnight is called the U.S. Open, the last of the year’s four majors, at the Billie Jean King Center in Flushing Meadow.

If there was a hard luck guy here yesterday, it was a 28-year-old German named Bjorn Pfau. He got in through the back door as a qualifier ranked No. 136 only to find himself looking at No. 1, Rafa Nadal, a bruiser seeking his third major of 2008. Pfau was named for Bjorn Borg, the great Swedish champion – but a luckless lad at the Open, zero for 10 years.

Still, in making Nadal pay attention, Pfau beaten 7-6 (7-4), 6-3, 7-6 (7-4), walked off with $ 18,500, which should keep him eating for a while. First prize in the first open was $ 14,000.

This reminded me that a U.S. Army lieutenant named Arthur Ashe worked the original Open in 1968 for 20 bucks a day, expenses payments. He was something called an amateur, a rare bird these days, perhaps an extinct species.

Sadly, Ashe, a humanitarian as well as a tennis Hall of Famer, is no longer with us for the US Tennis Association’s celebration of the 40th anniversary of “open” tennis. Kind readers, most of you will wonder what I’m talking about. After all, prize money has been the norm since 1968, which seems as long ago as the Dark Ages.

But there was a time, between 1881 and 1967, when the U.S. Championships was limited to true-blue (or so-called) amateurs, and the rewards were largely free lunch, and maybe a trophy. It was appropriate that in that horrific year of turmoil, 1968 – murders of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, Chicago cops vs Vietnam War protesters at the Democrat Convention, general strikes in France, Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia, riots in American cities – tennis should experience an upheaval. After years of agitation for allowing the outlaws – the pros – back into the big tent such as Wimbledon and the U.S. Championships, where they had starred as amateurs, British and American administrative factions forced the integration of amateurs and pros: open tennis.

It was about time because the pros, though a small band, were the game’s best: all-timers Rod Laver, Pancho Gonzalez, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad, Andres Gimeno, John Newcombe, Tony Roche to name seven. It was an amnesty for the banned pros, condemned to one-night stands and an occasional tourney such as the U.S. Pro at Longwood in Boston.

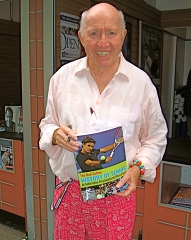

Tournament bosses were cautious. Wimbledon put up $ 62,000 for its first open. But USTA president Bob Keller, today a 95-year-old federal judge in Los Angeles, wanted to make a bigger splash — $ 100,000 for the inaugural US Open pot. Although many of his colleagues thought he was loony, that he would bankrupt the fragile USTA, Kelleher was right in believing that integrating the amateurs and pros would be a financial and artistic success, and now the USTA makes about $ 110 million on the tournament.

Amateur is an obsolete word. But 40 years ago, on grass at Forest Hills, the amateurs had some fun at the pros’ expense in the new world. Ashe and Clark Graebner made the semis. Ashe got there by beating Cliff Drysdale, now the debonair TV babbler, and Graebner knocked out the defending champion, Newcombe. Ray Moore, a South African who bravely spoke out against apartheid at home, and is one of the Indian Wells tournament proprietors, upset Gimeno in the first round.

A revelation was 40-year-old grandfather Pancho Gonzalez, returning to Forest Hills 19 years after winning the U.S. title, ascending to the quarters over Wimbledon runnerup Roche.

The pros were edgy. They had reputations to defend. Wimbledon champ, world No. 1 Rod Laver stumbled against Drysdale, who laughs, “I opened up the tournament for Ashe.” But Arthur did some heavy lifting in beating ex-champ Roy Emerson, Graebner, and for the title, Tom Okker of the Netherlands in five blazing sets. Though the loser, Okker won first prize, $ 14,000, because Ashe was ineligible as an amateur. Having won the U.S. Amateur title at Longwood two weeks previously, Arthur completed a never-to-be-repeated double: an amateur seizing both crowns. Of course he turned pro after his release from the Army.

Virginia Wade, the stylish Englishwoman who won the very first open that year, the British Hard Court Championship in April, as an amateur, quickly decided enough of that. She signed in as a pro at Forest Hills and stunned favored Billie Jean King for first prize, $ 6000. She said she preferred certified checks to tickets for tea time.

Well, we know that inflation has taken over, and Tom Okker’s $ 14,000 reward of 1968 looks like something this year’s champions would pass out as tips. Pursuing the titles held by Roger Federer and the abdicated Justine Henin, the champs will collect $ 1,500,000 apiece.

Seems sort of obscene for chasing a little yellow ball, doesn’t it? I hope the rich USTA is plowing back millions into youth programs. Not just to develop champions in this American time of talent scarcity, but just to put more kids on the courts to enjoy this wonderful game.

The $ 23.2 million pot is considerably heavier than the 100 grand risk Bob Kelleher took four decades ago, and the players work hard for it. But I still like to think back to skinny but heavy-hitting Ashe, lightly regarded, coming out of the pack of pros to land the big one.

I encountered his father, weeping, under the stands. He told me that his wife was unable to conceive. “We waited five years. Then a doctor a friend recommended helped her. But he was a sickly child. I thought we might lose him – now this…”

Of all the 40 opens there’s never been a better day. Anyone who knew Arthur would agree.

Leave a Reply